Talk

How Modernism arrived in Britain – Magnus Englund, director of The Isokon Gallery Trust

Co-author of Phaidon’s Walter Gropius: An Illustrated Biography, author of a further five books on design and architecture, retail specialist, director of The Isokon Gallery Trustand Trustee of the Robin and Lucienne Day Foundation, we grabbed some time with Magnus Englund to delve into his inside knowledge on modernism’s greats and the North London hub for abstract artists and radicals.

Who was Walter Gropius, the man behind the Bauhaus?

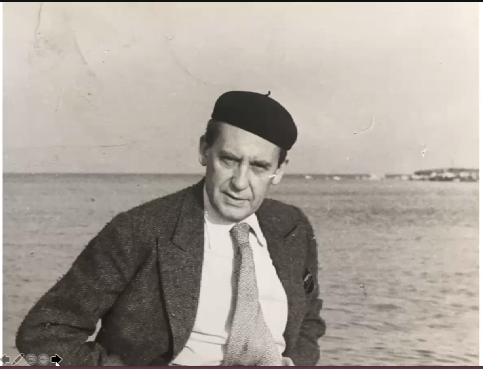

He came from a wealthy Berlin family and trained and worked as an architect from a young age. But Gropius was also a Prussian army officer on horseback during WWI. He was nearly killed several times and was awarded two iron crosses, so he was not a pen pusher but on the battlefields. It’s quite extraordinary that he then was able to apply himself to running a school of art and design immediately after the war, but the war had changed and radicalised him, and he wanted a better world.

Did running the Bauhaus hamper his career as an architect?

It was a source of conflict. Whilst running the Bauhaus, he was still a practising architect, that was the arrangement. He had started out in the office of Peter Behrens in 1908, where his fellow colleagues included both Mies van der Rohe and Charles-Édouard Jeanneret (later known as Le Corbusier), but he left Behrens and set up his own office. He seems a warm-hearted man from his personal letters, quite different from Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe who seem quite grumpy. Gropius enjoyed working in groups and was happy to recognise achievements of others.

The Bauhaus school was forced to close in 1933, although Gropius had already left in 1928. He briefly visited England in 1933, invited to Dartington Hall in Devon where there were talks of directing product design. It didn’t lead to a formal offer, although he did convert a 14th century barn into a theatre, which is maybe symbolic of British attitude to modernism at the time. He moved to England and Isokon Flats in 1934, and tried to find commissions, but it was difficult, and little was built. He was interviewed by the Royal College of Art, which at the time was incredibly set in their traditional ways, so they turned him down. However, the RIBA did recognise his importance; at the opening dinner for the new RIBA building on Portland Place, the seat of honour next to the king was given to Gropius. When Harvard was interviewing for a new director of architecture, they had two main candidates for the role: Mies or Gropius. Letters show that they found Mies the more interesting architect, but after meeting both they thought they’d have problems with Mies as a person, so Gropius was appointed instead. He left England for the USA in 1937.

Due to Gropius being so linked with the Bauhaus – which was no accident but orchestrated by him through a MoMA Bauhaus exhibition in 1938 masterminded with his wife Ise and Herbert Bayer – his later career and achievements after Harvard are lesser known. In this later period, he ran a large office and created some fascinating buildings, such as the US embassy in Athens, inspired by the Parthenon, and a masterplan for the University of Baghdad, which was never fully realised due to political upheaval in Iraq and Saddam Hussein coming into power. He also did the huge Gropiusstadt in Berlin.

He was incredibly hard working, right until the end of his life; when lying in his hospital bed, Gropius could look out of the window and see the construction of his latest building going up. He passed away in 1969. In his last ten years of his life, he was really a Brutalist.

When the Bauhaus School opened in 1919, it declared that they would admit ‘any person of good repute, regardless of age or sex..’. There’s been discussion of ‘masculine arts’ and women being ushered towards textiles.

You can’t apply 21st century norms to 1919 and see it through that lens. In fact, a majority of students at the Bauhaus were women, and there were also women in other workshops, such as metalwork, although men were in the majority there. The textile workshop was incredibly important for the school, as there was a period of hyperinflation, and the school was reliant on generating its own income. The only profitable products were textiles and wallpapers, so the women were very important for the survival of the school.

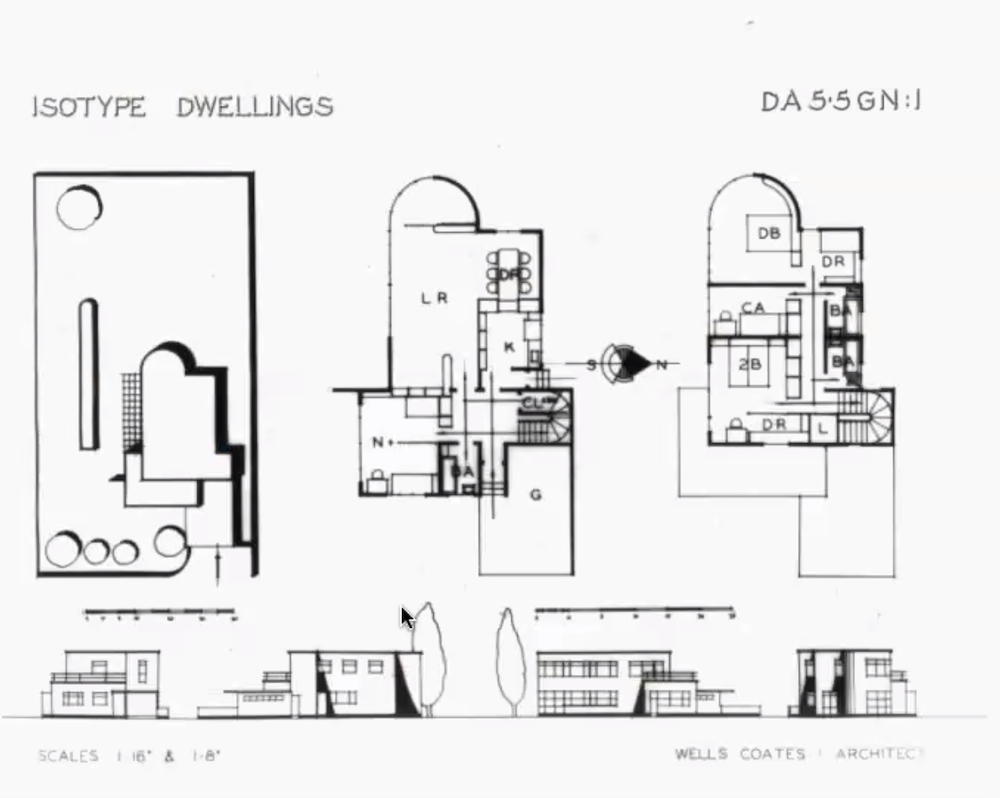

The Isokon building introduced the idea of minimal living and Modernism to Britain, all thanks to the relationship and combined heads of the Pritchards and architect Coates. A magic moment. Can you tell us some more about their meeting of minds?

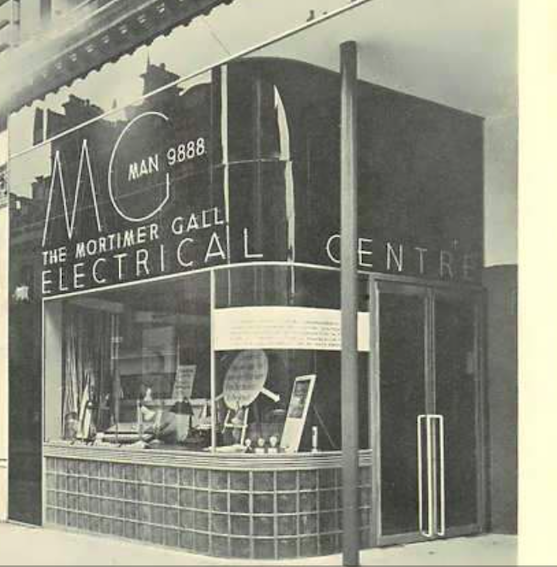

Both Jack Pritchard and Wells Coates had – separately – discovered Le Corbusier at the Paris World Fair in 1925, which was a life changing experience for them. Molly Pritchard was a sharp intellect and had moved in radical Bloomsbury circles in the 1920s, and she was the one who drew up the brief for how the Isokon Flats should function. She also had an affair with Coates after having married Jack Pritchard, but that was not so strange as their whole attitude was to reject Victorian values. Jack Pritchard and Wells Coates visiting the Bauhaus school in Dessau in 1931 is arguably what gave Isokon Flats its final form, there are details like the balconies and the stairwell tower than are directly influenced by Walter Gropius architecture. Little did they know then that Gropius would be one of the first residents.

Was it by chance that so many notable artists / designers congregated at the Isokon building?

The Isobar was a real pull, it held art exhibitions and served good food and drinks. The Mall Studios were just around the corner, built specifically to be artist studios. The occupiers included Barbara Hepworth, Ben Nicholson and Herbert Read (founder of the ICA), all who changed the face of 20th century British art. Henry Moore lived and worked nearby too. At the time, due to the rise of fascism in Europe, there were many refugees arriving in London. Piet Mondrian’s garden backed onto the Mall Studios when he lived in London for two years from 1938, after escaping Paris. There was an anti-Nazi German culture club close to the Mall Studios, where they put on theatre plays and concerts. Naum Gabo lived on Lawn Road, and just on the edge of Hampstead Heath was Erno Goldfinger at 2 Willow Road. All of them were friends with Jack & Molly Pritchard. Many central European refugees opposing Hitler were also communists, which partly overlapped with the artistic community. Within the Isokon Flats, there were five people who worked for Soviet intelligence, and many other people in the area were under investigation by the MI5, so it must have been a tense time.

Buy Walter Gropius: The Illustrated Biography’, Phaidon, by Magnus Englund and Leyla Daybelge

Buy Isokon and The Bauhaus in Britain, Batsford books, by Magnus Englund and Leyla Daybelge

Find out more and support The Isokon Gallery Trust isokongallery.org

Visit the ‘Modernism at the Mall: The Hampstead Studios where Barbara Hepworth, Ben Nicholson and Herbert Read changed the face of British art – until late October 2023.