Talk

A life in art – Robin Vousden, Howard Hodgkin’s long-term art dealer

A lesson in following your heart – and being encouraged to do it – working hard and by his accounts ‘with wonderful luck’, and how to survive in the art world via the Whitworth in Manchester, Anthony d’Offay in London, Marian Goodman in New York, and Gagosian worldwide, with a bank of good stories in between. His professional career began in the 1970s when ‘there was almost no money in the contemporary art world, very few collectors and artists were living on a cup of tea.’

We had the great pleasure in talking to Robin Vousden, curator, gallerist and long-term dealer and friend of the late Sir Howard Hodgkin, CH.

How did your relationship with Howard Hodgkin come about?

Howard Hodgkin has been part of my visual, mental and emotional landscape for almost half a century.

I became aware of Howard’s work first in the mid-1970s when a museum exhibition, organised by Nicholas Serota, travelled from the Museum of Modern Art Oxford to the Turnpike Gallery, Leigh, a recently opened arts venue in Greater Manchester. These intense, radiant, intelligent and original paintings were a revelation. I had never seen anything like them.

Later, while still at the Whitworth, I borrowed a great work of Howard’s, ‘Cafeteria at the Grand Palais’, for an exhibition of paintings belonging to the Bernstein family and their famous company, Granada. We put Howard’s painting on the cover of the catalogue.

When the show came down, we wrote to the artist to say how much we missed his work and wondered if he might have a painting in the studio that we could purchase for the museums’ collection? After a short period, my boss in those days, Francis Hawcroft, was offered ‘Interior at Oakwood Court’, and snapped it up. It’s a powerful work.

By the early 1980s I had the job I had always wanted, curator of modern art at the Whitworth Art Gallery, University of Manchester. Since we were a collecting and purchasing museum, I would visit London regularly to go around the modern and contemporary galleries to keep up to date.

By far the most exciting and impressive dealers’ gallery at the time was Anthony d’Offay.

Anthony and his small team had two premises in Dering Street, which was at the Oxford Street end of New Bond Street. There I could see not only the Bloomsbury, Camden Town and Vorticist painters of early British modernism but even more excitingly, new work by Joseph Beuys, Gilbert and George and Richard Long. It was thrilling to visit, maybe to chat to Anne Seymour d’Offay, and feel as though I was witnessing something new and wonderful and international coming into being.

I bought a painting by David Bomberg from Anthony and a postcard sculpture by Gilbert and George. I tried my best to persuade Francis to buy a ravishing flint line sculpture by land artist Richard Long, which I thought could perfectly complement the Gallery’s distinguished collection of landscape art. Francis said ‘I shan’t always be here’. So that was that for a moment.

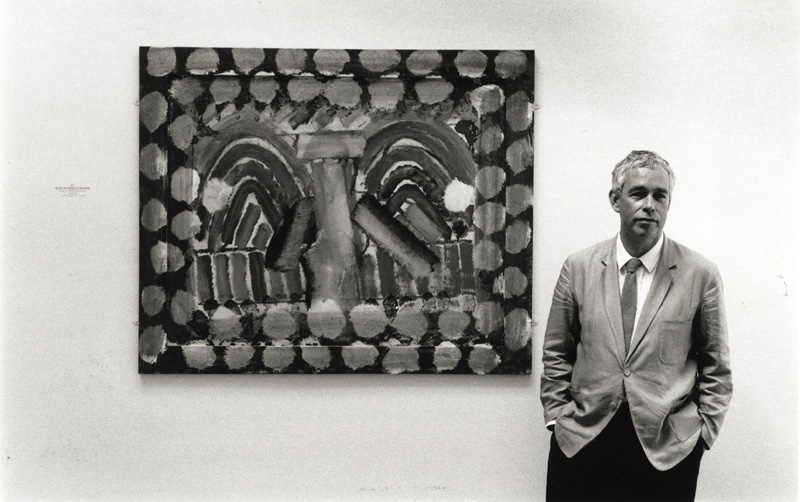

Those experiences, and the memorable encounter of Joseph Beuys’ magnificent installation, ‘dernier espace avec introspecteur’ (Staatsgalerie Stuttgart) meant that when Anthony invited me to join his gallery as a director in early 1984 there was only one answer.

‘Yes please’.

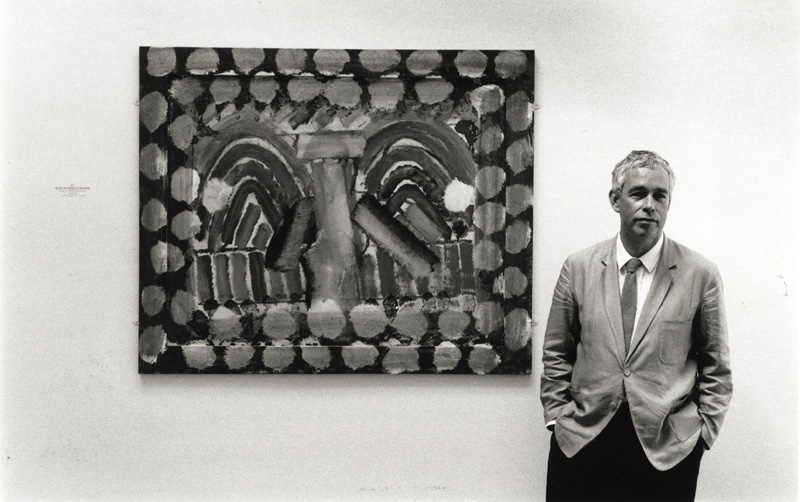

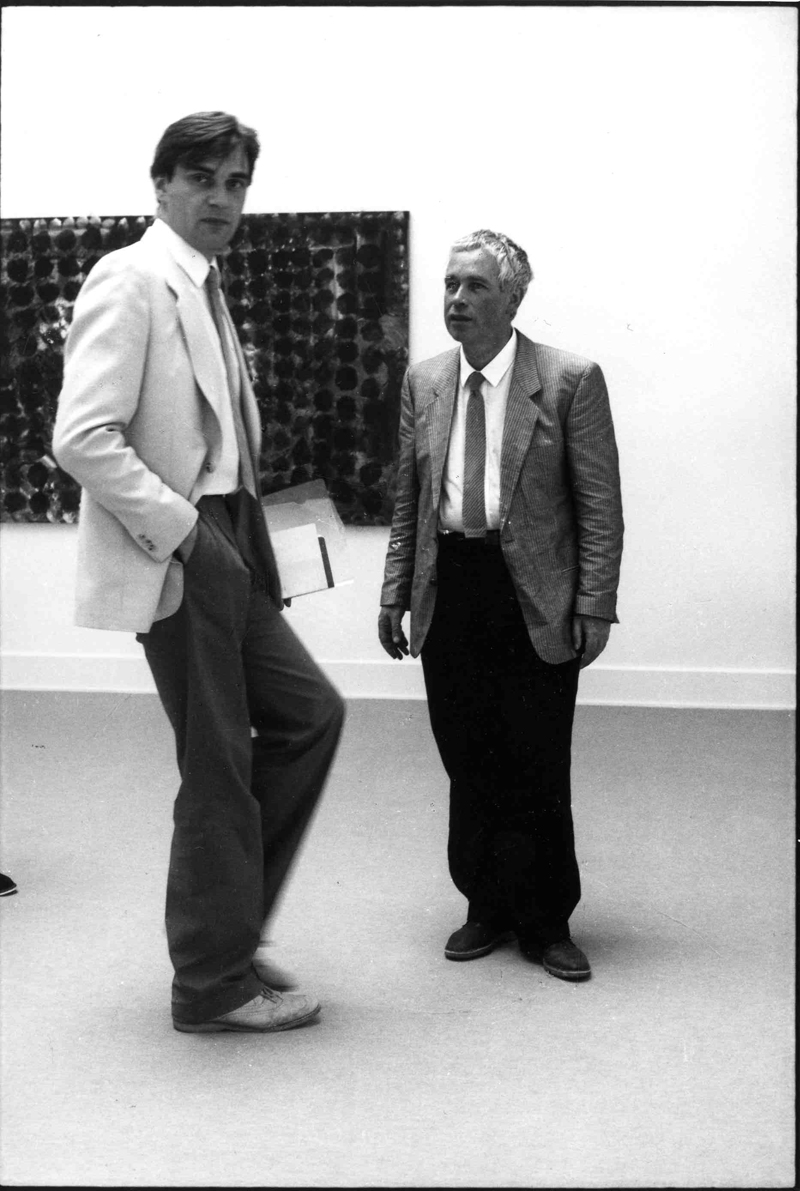

I was packed off to Venice in pursuit of Howard Hodgkin almost as soon as I arrived at d’Offay. Howard’s exhibition in the British Pavilion of the Biennale was a triumph. The talk of Venice. Howard’s New York dealer, Larry Rubin, threw a great party for the artist, shipping us all by boat out to the magical island of Torcello and a gala lunch at the Locanda Cipriani there. An affair to remember.

Can you tell us more about ‘A representational depiction of emotional situations’.

Howard never fitted into a particular genre. Friends and near contemporaries included Peter Blake, Patrick Caulfield, Richard Hamilton and David Hockney and other artists associated with ‘Pop’. Other peers like Richard Smith and Robyn Denny where amongst the most ambitious abstract painters of the time.

You might say that Howard’s work is the visual depiction of the artist’s memory of an emotional state, or states. An extraordinary level of control and spontaneity is needed to achieve this. The painter must control his own intense emotion in order to manipulate our response.

Howard once described himself as being like Kay, the little boy held captive by the Snow Queen, in Anderson’s eponymous fairy tale.

‘I need a splinter of ice in my heart to achieve the result that I want.’

Howard’s paintings are multi-layered. They carry the history of their own making with them. Once the viewer is engaged, each painting becomes a serious playground for the eye and heart. Pictorial space is conjured up out of nowhere, light emerges from the back of the painting, enlivening and illuminating both the present moment and the recollected past.

Howard’s paintings are inexhaustible and inimitable.

An extraordinarily bright man, Howard seemed at times to be more intelligent than everyone else in the room put together. You couldn’t fool him, not for a moment. He might try to fool you, but you both knew you were being played with.

To be teased by Howard was a delight. At the same time, Howard’s own emotion could overwhelm him. He refused to be present when all but the most trusted family and friends were in the studio with the work. A wrong word, a clumsy or inept response, could throw the artist off balance for days.

The motto of the famous Scottish clan Drummond is ‘Gang warily’. The same advice could sensibly be offered to a visitor in Howard’s studio. Gang warily indeed. Here be dragons…

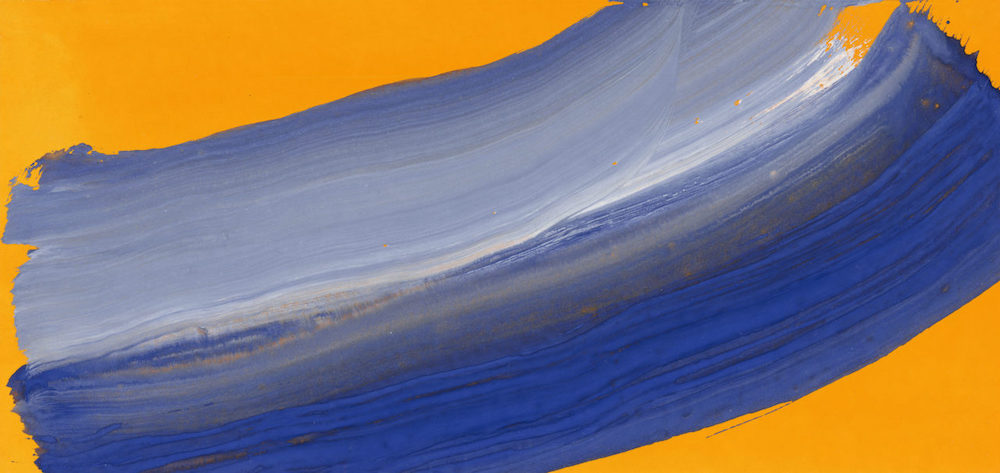

In the later part of his career, the paintings became more simple and yet more profound. Much of the work was done in the artist’s head. Looking and thinking took longer than painting. He seemed to be hoping to make a painting at last which was but a single brushstroke. Howard’s penultimate picture, ‘Over to You’, pretty well achieves this. An astonishing work.

Can you tell us about Hodgkin’s avid collecting throughout his life?

You should really ask this question of Howard’s life time partner, Antony Peattie. He had to live with Howard the collector. I was only ever ‘visiting’.

Howard would show me things he had bought, Islamic tiles, fragments of carpet or an Indian picture. It was to share his experience of them and transmit his pleasure, the same sense of discovery and delight. It was rather like how he felt about his art. He cared enormously how you responded. He liked to invite you in to see what he was up to.

I collect pots – you can see what the potter is doing as the vessel comes into being.

With Howard’s paintings, your imagination joins in with the loaded brushstroke and you become at one with the paint. The work becomes a theatre. Van Dyck and Thomas Lawrence taught us this. The viewer’s pleasure comes from the fact and the spirit of the brushstroke. If another visitor fails to get this, you question a hasty judgement. Only after some time can they penetrate the painting’s space. Discover its many secrets and its joy.

What’s the one thing you’ve learnt – the most valuable advice for a budding art dealer?

‘It’s the art, stupid’ to misquote President Clinton’s strategists James Carville. Without artists, we have no art and we are all out of a job. The artists give us everything they have, all that they are. In return they have to feed off us, to depend upon us, for attention and support. Only they can perform this extraordinary alchemy, which Dylan Thomas put perfectly:

‘The world is never the same once a good poem has been added to it.’

Howard Hodgkin added many good ‘poems’ to the world. Our job is to learn them.

Learn more from howard-hodgkin.com

See our latest handknotted rug, ‘Indian Sea’, produced in association with the Howard Hodgkin Estate.

Main photograph: Howard Hodgkin at the British Pavilion for the XLI Venice Biennale, 1984. Image courtesy of the British Council. Artwork: ‘D.H. in Hollywood’, 1980.